Laude XCII: Donna de Paradiso

The Twin Poems: Donna de Paradiso and Stabat Mater

Detail: Giotto, Lamentation , c.1305, fresco, Scrovegni Chapel, Padua.

The laude Donna de Paradiso and the hymn Stabat Mater are the best known of all of Jacopone da Todi’s works. Both address the same theme – the suffering of Mary, as a mother, at the death of Jesus at Calvary – and can therefore be considered as ‘twin poems’. Like all twins, however, there are also important differences between them.

Donna de Paradiso is a moving and intensely realistic description of the Passion of Christ written, like all Jacopone’s laudi, in the Umbrian vernacular. Jacopone wanted to present the Passion as a drama, true in all its cruelty and humanity. So he chose to describe it through the suffering of Mary, because there is no pain greater than that of a mother witnessing the torture and killing of her own son. For Jacopone, the Madonna is the icon of suffering, while the Cross is the icon of love. You can read Donna de Paradiso, with English translation here and Italian translation here.

Stabat Mater pictures the same scene but is primarily an appeal, addressed by the poet to the Virgin, to join with her in her suffering and in love for the crucified Christ. It is written in Latin, with the rhythmic cadence of a prayer and presents the aspiration of every believer to identify with the crucified God and to lose oneself in his love. You can read it, with English translation here and Italian translation here.

The expressive power of these two poems is enhanced by their communicative and artistic formats, which are very different from those of traditional poems:

Donna de Paradiso is widely regarded as the first work of Italian theater and is perhaps the most translated and most performed Italian dramatic work in the world.

Stabat Mater has been set to music remarkably often, possibly more often than any other poem over the past seven centuries.

These two facts alone, we hope, will attract the interest of our readers and spark a desire to read, meditate and enjoy these two poems.

Fra Angelico; Crucifixion; c.1420–23; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The connecting point

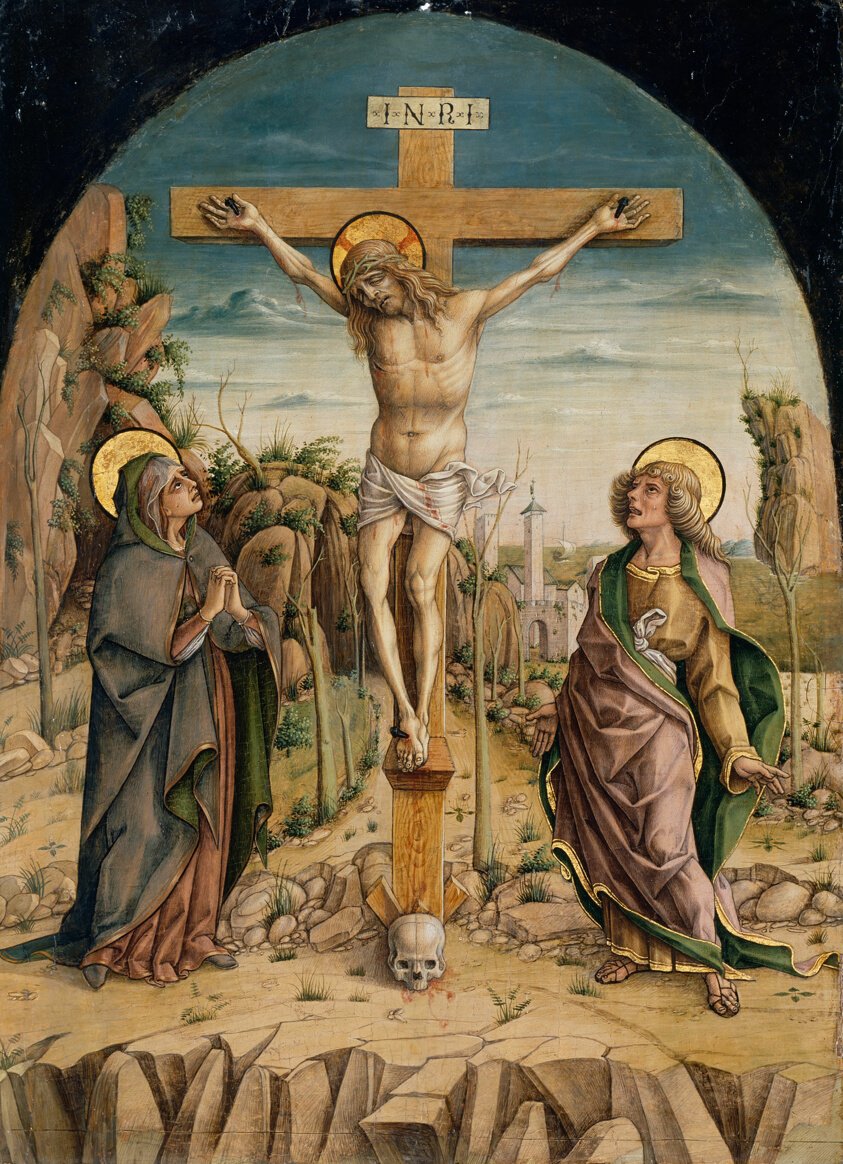

Despite these differences, the two poems are connected by a shared perspective in the physical setting pictured by Jacopone when describing the culmination of the Passion. Most medieval (and later) depictions of the Crucifixion show Jesus raised high above the ground on a tall cross, while Mary is often shown swooning helplessly on the ground nearby.

In contrast, Jacopone envisages close visual and vocal contact between the crucified Christ and his weeping Mother, standing next to the cross. The first three lines of the Stabat Mater present this scene like a photographic snapshot:

Stabat Mater dolorosa The grieving Mother stood

iuxta crucem lacrimosa beside the cross weeping

dum pendebat Filius while her Son was hanging

Stabat (‘stood’ ): The poet envisages Mary standing, not swooning. A strong woman, she wanted to be next to her dying Son, so that he could have before his eyes, until the end, the face of one who had loved him most of all, of one who would never abandon him. She must not let go and therefore ... stabat!

iuxta crucem means ‘next to the cross’, not ‘at the foot of the cross’. In both poems Jacopone seems to picture Jesus on a low cross, raised not much higher than those standing on the ground beside him (something largely borne out by what we now know of the historical reality of crucifixion). This scenario means that the Mother could bring her face close to that of her dying Son and perhaps hear some words, uttered with great difficulty and pain by him. It is an extraordinary contextualization of the Crucifixion in a less symbolic and more realistic form than most other representations.

dum means ‘for as long as’. The Mother remained standing beside her Son for as long as he remained on the cross.

Carlo Crivelli, Crucifixion, c. 1487, tempera on panel, Art Institute of Chicago

pendebat (‘hung’) presents another element of reality. Most representations show Jesus almost upright on the cross, with arms outstretched and often with his face pointed upwards. In reality, however, he would have ‘hung’ like a rag, slumped over under his own weight and with drooping head, until he suffocated. Once again Jacopone departs from artistic conventions to present a more accurate and realistic view.

Stunning

Of these three initial lines, Desmond Fisher wrote:

In Latin, the sonorous quality of those first nine words is stunning. The regular beat of the softly rhyming polysyllable words give the three short lines a depth and a strength no translation could surpass.

There can be no better reason to dispel doubts about Jacopone's authorship of the Stabat Mater. These three lines present the necessary condition for understanding Donna de Paradiso, where the long and intimate dialogue between Mary with her dying son requires the situation that the Stabat Mater describes. Furthermore, the beauty and evocative power of these nine words clearly convinced Desmond Fisher that only a great poet – like Jacopone – could have composed them.

Evgraf Semenovich Sorokin, Crucifixion, 1873

A deep sigh

The two poems share another moving detail. In Donna de Paradiso (verse 29) the Mother says “Son … your soul has gone from you (l’alma t’è ‘scita)”, reflecting the experience of many who closely assist a dying person. At the final moment, many dying persons indeed emit a last breath, like a deep sigh. The Mother of Jesus was close enough to hear this sigh and understand that it was the end.

In the Stabat Mater, verse 8 reads:

Vidit suum dulcem natum She saw her sweet child

moriendo desolatum dying desolate

dum emisit spiritum as he released his spirit

The final word, spiritum, means ‘breath’ as well as ‘spirit’. So ‘dum emisit spiritum’ can be translated ‘as he released his breath’. Whether ‘breath’ or ‘spirit’ is intended, the phrase has essentially the same meaning as ‘l’alma t’è ‘scita’ in Donna de Paradiso. The two poems paint precisely the same picture as Mary, standing next to her crucified Son, hears his long, final sigh and realises that he has died.

Stabat Mater and Donna de Paradiso are twin poems, then, with different characteristics and purposes but with the same subject, the same inspiration and many detailed similarities of perspective.